I have a new blog listed on the sidebar called SKILLING FAMILY MEMORIES in which I am blogging chapter by chapter my mother-in-law, Norma Skilling Jackson's book about her family history from Scotland to Ontario. I will be adding photographs later. Please check it out.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Tracing Lena Huckan – Part One (Ben Nevis House) Guest Post by Christian Cassidy (This Was Winnipeg)

After writing my "Letters to a Dead Great-Aunt" series, I made the acquaintance of Christian Cassidy, a local Winnipeg historian who writes several blogs. He offered to do some additional research for me in Winnipeg to uncover more about the life and death of my Great-Aunt Michalena in a hotel fire in 1918. Here in his guest post is Part One, based on information found in the 1915 Henderson Directory for Winnipeg. Lena was listed as living in Ben Nevis House at 42 Dagmar Street.

Tracing Lena Huckan

Ben Nevis House

The name "Ben Nevis House" (named for the highest mountain in Great Britain) does not appear in ads until June 1907.

An advertisement in 1917 says that Ben Nevis House is the "first house from Notre Dame". If that is the case then this is a picture of Lena‟s neighbourhood circa 1903. It's a photo looking up Notre Dame FROM Dagmar so that would be her streetcar, taking her to and from the city core.

Could Lena have worked at Ben Nevis as well as live there, similar to what she did (later) at the Riverview (Hotel)? Ben Nevis House routinely had ads similar to this in the papers. From March 14, 1913:

Ben Nevis House was a regular advertiser and not just with little classified ads but larger ones in amongst city hotels; so it may have been a little high end, perhaps out of Lena's price range.

Other mentions of Ben Nevis around the time she may have been living there:

Perhaps had some fun while she lived there….

Caledonian Sports Witnessed by Large Crowd at Horse Show Building Last Night. October 5, 1910 MB Free Press

Close on 3,000 people witnessed the first annual Caledonian games at the Horse Show amphitheatre last night. Mixed in with the Scotch music and dancing were the more common athletic sport.

Tug- of war - Caledonians swept everything before them in this contest. They first defeated the Electrical Union team in two straight -pulls and then did the same thing, only more easily, to a team

from the Ben Nevis house.

The Neighbourhood

All of the houses on that first block of Dagmar, and parallel streets, are now gone. That stretch of Notre Dame is fairly commercial with some light industrial and as the Notre Dame buildings expanded, the houses directly behind them disappeared.

These are photos of houses within a couple of blocks of Ben Nevis House and, presumably, would be similar in size or style. Dagmar wasn't noted for being a remarkable street in comparison to the rest of the neighbourhood.

Central Park

Given where she lived, she definitely would have visited Central Park, just a couple of blocks to the south. ( http://winnipegdowntownplaces.blogspot.com/2010/09/downtown-places-central-park.html )

Central Park was one of Winnipeg's first parks. It was originally a natural space, but

by the time she lived there, the park would have boasted tennis courts, a bandshell and the Waddell Fountain. It was a very popular place and you can see the treeline from where she lived.

Some of the old houses and buildings exist around the park. Knox Church (above) was built between 1914 and 1918 (the war interrupted). The Warwick, Winnipeg's first upscale apartment block, was there in 1909. (for more on the Warwick: http://winnipegdowntownplaces.blogspot.com)

One feature that was unveiled in 1914 was the Waddell Fountain. It was an attraction unto itself. This summer, in fact, the fountain was re-installed after a complete rebuild and upgrade.

More on the fountain and the interesting story behind it http://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/hrb/prov/p078.html)

Other period shots of Central Park:

http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/postcards/PC002133.html

Tracing Lena Huckan

Ben Nevis House

In 1903 advertisements begin to appear for "rooms for rent" at 42 Dagmar. At first it was three, then four rooms.

The Morning Telegram -- July 19, 1907

The name "Ben Nevis House" (named for the highest mountain in Great Britain) does not appear in ads until June 1907.

Notre Dame from Dagmar ca. 1903 Source: http://virtual.heritagewinnipeg.com/windowPhoto.php?fileNum=%2002-299&tName=downtown

An advertisement in 1917 says that Ben Nevis House is the "first house from Notre Dame". If that is the case then this is a picture of Lena‟s neighbourhood circa 1903. It's a photo looking up Notre Dame FROM Dagmar so that would be her streetcar, taking her to and from the city core.

Could Lena have worked at Ben Nevis as well as live there, similar to what she did (later) at the Riverview (Hotel)? Ben Nevis House routinely had ads similar to this in the papers. From March 14, 1913:

Classified (Manitoba Free Press)

SMART GIRL WANTED AT ONCE FOR

upstairs and wait table. $20. Ben Nevis House. 42 Dagmar Street.

SMART GIRL WANTED AT ONCE FOR

upstairs and wait table. $20. Ben Nevis House. 42 Dagmar Street.

Ben Nevis House was a regular advertiser and not just with little classified ads but larger ones in amongst city hotels; so it may have been a little high end, perhaps out of Lena's price range.

Other mentions of Ben Nevis around the time she may have been living there:

The Voice -- August 3, 1917

Perhaps had some fun while she lived there….

Caledonian Sports Witnessed by Large Crowd at Horse Show Building Last Night. October 5, 1910 MB Free Press

Close on 3,000 people witnessed the first annual Caledonian games at the Horse Show amphitheatre last night. Mixed in with the Scotch music and dancing were the more common athletic sport.

Tug- of war - Caledonians swept everything before them in this contest. They first defeated the Electrical Union team in two straight -pulls and then did the same thing, only more easily, to a team

from the Ben Nevis house.

The Neighbourhood

All of the houses on that first block of Dagmar, and parallel streets, are now gone. That stretch of Notre Dame is fairly commercial with some light industrial and as the Notre Dame buildings expanded, the houses directly behind them disappeared.

Period House near Bannatyne Ave. and Notre Dame http://www.flickr.com/photos/christiansphotos/5138797512/

There are still pockets of period houses in the neighborhood. Period houses on Bannatyne Ave http://www.flickr.com/photos/christiansphotos/5138186391

These are photos of houses within a couple of blocks of Ben Nevis House and, presumably, would be similar in size or style. Dagmar wasn't noted for being a remarkable street in comparison to the rest of the neighbourhood.

Central Park

Central Park ca. 1918 http://www.virtual.heritagewinnipeg.com/windowPhoto.php?fileNum=%2002-194&tName=downtown

Street around Central Park ca. 1912 http://www.virtual.heritagewinnipeg.com/windowPhoto.php?fileNum=%2002-071&tName=downtown

Given where she lived, she definitely would have visited Central Park, just a couple of blocks to the south. ( http://winnipegdowntownplaces.blogspot.com/2010/09/downtown-places-central-park.html )

Central Park was one of Winnipeg's first parks. It was originally a natural space, but

by the time she lived there, the park would have boasted tennis courts, a bandshell and the Waddell Fountain. It was a very popular place and you can see the treeline from where she lived.

Some of the old houses and buildings exist around the park. Knox Church (above) was built between 1914 and 1918 (the war interrupted). The Warwick, Winnipeg's first upscale apartment block, was there in 1909. (for more on the Warwick: http://winnipegdowntownplaces.blogspot.com)

One feature that was unveiled in 1914 was the Waddell Fountain. It was an attraction unto itself. This summer, in fact, the fountain was re-installed after a complete rebuild and upgrade.

More on the fountain and the interesting story behind it http://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/hrb/prov/p078.html)

Other period shots of Central Park:

http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/postcards/PC002133.html

Copyright © 2010, Christian Cassidy for Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Building the Alaska Highway: Dad's Story

Last Thursday on Remembrance Day I planned to write about my Dad’s contribution to the war effort, building the Alaska Highway. My parents, married in October 1939 just weeks after WW11 broke out, were living and working in Toronto. By 1940 in Canada conscription had been introduced for home defence and Dad was worried. After witnessing WW1 as a child in Europe, he had no appetite for active service.

In 1941, months after I was born, my father took a job with Curran and Briggs, a paving and construction company with the first Canadian contract to work on the construction of the Alaska Highway. My father made that decision without consulting my mother, so she was very angry he was going off for a year, leaving her with a newborn baby and a rooming house to manage in downtown Toronto. From his point of view, it was an opportunity to work at his trade as a welder and earn a lot of money. After finishing a welding course at night school, he’d found it difficult to obtain work in his trade in the 1930s and continued to work in the restaurant business out of necessity. He first heard about the job from a friend, Fred Caruk, who owned Master Welding in Port Credit, just west of Toronto. When Dad was offered a chance to work as welder maintaining all machinery and equipment for this paving company, he saw it as a great chance and a bit of an adventure. It also gave him a way of contributing to the war effort.

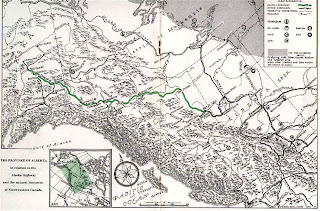

An Alaska Highway had been proposed and debated in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until fear of a Japanese invasion via Siberia and the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941, that such a road, as a supply route, was thought to be essential for the defence of North America. On February 11, 1942 President Roosevelt officially authorized work to begin by the United States Army Engineer Troops.

According to family lore, my father was already in Alaska by September 1941. He travelled by train from Union Station in Toronto to Edmonton and from there to Dawson Creek, BC. Over the year he would travel with his firm as they advanced construction from Dawson Creek to the highway's middle point. Others were working from Fairbanks, east to the middle point at around Watson Lake.

Working and living conditions were extremely difficult with temperatures ranging from 90 degrees F. to -70 degrees F. Swamps, rivers, ice, cold, mosquitoes, flies and gnats tested the men daily. Most camps were kept open and machinery operated on a 22 hour basis, with 11 hour shifts. Trying to maintain equipment not designed for such conditions, was an ongoing challenge to the creativity of men like my father.

While Dad was in Alaska, Mom would tell me stories about him and read his letters to me. After about a year my dad came home for a two month visit when I was about 18 months old. I have no recollection of his visit in October 1942, only the family story that I cried and clung to him in Union Station when he boarded the train to return.

The highway officially opened November 1942, though improvements continued to be made for months and years later. Dad worked in Alaska for another 4 months before coming home for good in about February 1943, just before I turned two years old.

I have no memory of his return or the events that followed. The story is that he returned with $30,000 and invested it in a business partnership that went sour. The money vanished and Mom continued for another seven years to run the rooming house and save her meager dollars for a down payment on her dream house in the suburbs. Ashamed of his bad judgement and grateful for Mom's forgiveness, my father started his own welding business, Ontario Collision and Welding. He persevered and was successful.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

In 1941, months after I was born, my father took a job with Curran and Briggs, a paving and construction company with the first Canadian contract to work on the construction of the Alaska Highway. My father made that decision without consulting my mother, so she was very angry he was going off for a year, leaving her with a newborn baby and a rooming house to manage in downtown Toronto. From his point of view, it was an opportunity to work at his trade as a welder and earn a lot of money. After finishing a welding course at night school, he’d found it difficult to obtain work in his trade in the 1930s and continued to work in the restaurant business out of necessity. He first heard about the job from a friend, Fred Caruk, who owned Master Welding in Port Credit, just west of Toronto. When Dad was offered a chance to work as welder maintaining all machinery and equipment for this paving company, he saw it as a great chance and a bit of an adventure. It also gave him a way of contributing to the war effort.

|

| Jack Zaryski Pulling Welding Machine for Curran & Briggs c. 1942 |

An Alaska Highway had been proposed and debated in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until fear of a Japanese invasion via Siberia and the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941, that such a road, as a supply route, was thought to be essential for the defence of North America. On February 11, 1942 President Roosevelt officially authorized work to begin by the United States Army Engineer Troops.

According to family lore, my father was already in Alaska by September 1941. He travelled by train from Union Station in Toronto to Edmonton and from there to Dawson Creek, BC. Over the year he would travel with his firm as they advanced construction from Dawson Creek to the highway's middle point. Others were working from Fairbanks, east to the middle point at around Watson Lake.

|

| Route of Alaska Highway Govt. of Alberta |

|

| Jack Zaryski aka. Johnny the Welder |

While Dad was in Alaska, Mom would tell me stories about him and read his letters to me. After about a year my dad came home for a two month visit when I was about 18 months old. I have no recollection of his visit in October 1942, only the family story that I cried and clung to him in Union Station when he boarded the train to return.

The highway officially opened November 1942, though improvements continued to be made for months and years later. Dad worked in Alaska for another 4 months before coming home for good in about February 1943, just before I turned two years old.

|

| Alaska Highway Dawson Creek, B.C. c. 1940s |

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Working in Cranberry Portage, Manitoba 1930

My Mother celebrated her 97th birthday a few weeks ago. Still alert and mobile, she says she might now make it to 100! A remarkable feat for someone who never knew as a child if they would have enough to eat. She went to work at fifteen to help the family. In 1930, when she was sixteen, she ended up working in Cranberry Portage, a booming frontier town in northern Manitoba.

In 1928, a devastating forest fire had swept a large part of the old town built of logs and wood. I asked my mother to tell me how she came to work in Cranberry Portage, Manitoba in 1930, just two years after the big fire.

She told me: "jobs just seemed to land in my lap, one after another".

One day she was walking down the street with a friend in Winnipegosis and saw a "Help Wanted" notice in a store window. A woman was looking for a person to come to Cranberry Portage with her family to help cook and look after their three children. Her husband worked at a gravel pit while the woman had a job cooking for a camp of men who worked along the railway track outside of Cranberry Portage. Mom couldn’t remember if it was a mining camp or a lumber camp. Most likely it was a camp for C.N.R. workers who were laying eighty-seven miles of railroad track to a wilderness tent town of Flin Flon. Mrs. Anderson, Mom recalled, was a woman of Polish and Icelandic descent. While Mom worked for her for about a month, they lived in a tent which was actually a temporary frame building with a canvas roof tied on top.

When Mrs. Anderson no longer needed Mom, she was offered a job at the Redwing Café Store Bakery as a waitress and helper, replacing a Swedish nineteen year old boy who had gone home for a month. After a month, Mom was asked to stay on, and the other hired girl left to help relatives who had just come to town to open a restaurant.

"Hutch" and his family owned the café. His wife was Norwegian or Swedish from Seattle, Washington and his mother also lived with them. Mom recalls she worked there for three or four months. She knows for sure she was there for her seventeenth birthday on October 23rd. Likely she went for the summer season in June or July and left in November.

When I think about what I was doing at age sixteen or seventeen, or what my children and grandchildren are doing, I think my mother was courageous to take a job so far from her home in Sclater, Manitoba and go to a northern town full of mostly men of a hundred different nationalities. She set the adventure bar high for all of us and we are so grateful. Happy Birthday, Mom.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

In 1928, a devastating forest fire had swept a large part of the old town built of logs and wood. I asked my mother to tell me how she came to work in Cranberry Portage, Manitoba in 1930, just two years after the big fire.

She told me: "jobs just seemed to land in my lap, one after another".

One day she was walking down the street with a friend in Winnipegosis and saw a "Help Wanted" notice in a store window. A woman was looking for a person to come to Cranberry Portage with her family to help cook and look after their three children. Her husband worked at a gravel pit while the woman had a job cooking for a camp of men who worked along the railway track outside of Cranberry Portage. Mom couldn’t remember if it was a mining camp or a lumber camp. Most likely it was a camp for C.N.R. workers who were laying eighty-seven miles of railroad track to a wilderness tent town of Flin Flon. Mrs. Anderson, Mom recalled, was a woman of Polish and Icelandic descent. While Mom worked for her for about a month, they lived in a tent which was actually a temporary frame building with a canvas roof tied on top.

|

| Mrs. Harry Anderson Cranberry Portage, MB 1930 |

When Mrs. Anderson no longer needed Mom, she was offered a job at the Redwing Café Store Bakery as a waitress and helper, replacing a Swedish nineteen year old boy who had gone home for a month. After a month, Mom was asked to stay on, and the other hired girl left to help relatives who had just come to town to open a restaurant.

|

| My mother, Jean Zaretsky far right, Petersen/Schamerhorn family, owners of Redwing Cafe Store Bakery, Cranberry Portage, MB 1930 |

"Hutch" and his family owned the café. His wife was Norwegian or Swedish from Seattle, Washington and his mother also lived with them. Mom recalls she worked there for three or four months. She knows for sure she was there for her seventeenth birthday on October 23rd. Likely she went for the summer season in June or July and left in November.

|

| Jean Zaretsky age 17 Cranberry Portage, MB 1930 |

When I think about what I was doing at age sixteen or seventeen, or what my children and grandchildren are doing, I think my mother was courageous to take a job so far from her home in Sclater, Manitoba and go to a northern town full of mostly men of a hundred different nationalities. She set the adventure bar high for all of us and we are so grateful. Happy Birthday, Mom.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

E-book Sales, Romance and Memoir Publishing

About a year ago Sandy Naiman, a journalist friend I hadn't seen for many years, asked me if my book would be coming out in print or E-book format. No one had ever asked me that question. I was taken aback and replied: "Oh, print, of course." Now I'm reconsidering my answer.

This week the stats came out on E-Book sales: up 172% in August and almost 193% for the year. I sat up and took more than passing notice because a couple of other things happened this week to make me stop and think about E-Books.

E-book Sales Jump 172% in August

At this month's WCDR breakfast meeting this month I met a writer who has 4 different E-Book publishers for her novels and is making a passable living from royalties after only one year. She specializes in romance, fantasy novels; there is a big market and many publishers for this genre.

The advantages for the publisher are obvious: lower costs, less risk. But the advantage for the emerging writer are that a publisher may willing to take a risk on you and the royalties may be greater than in print books.

Another wake-up call was the news that my cousin Mary self-published her memoir in Naples, Florida and though she has printed copies for family members, has also posted E-Book versions on a wesite for others to read. Congratulations, Mary! This is an admirable achievement and will be appreciated by many. I have posted a link to the left of this post.

Now I will investigate the possibility of an E-Book publisher for my memoir. Are you considering an E-Book for yours?

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

This week the stats came out on E-Book sales: up 172% in August and almost 193% for the year. I sat up and took more than passing notice because a couple of other things happened this week to make me stop and think about E-Books.

E-book Sales Jump 172% in August

At this month's WCDR breakfast meeting this month I met a writer who has 4 different E-Book publishers for her novels and is making a passable living from royalties after only one year. She specializes in romance, fantasy novels; there is a big market and many publishers for this genre.

The advantages for the publisher are obvious: lower costs, less risk. But the advantage for the emerging writer are that a publisher may willing to take a risk on you and the royalties may be greater than in print books.

Another wake-up call was the news that my cousin Mary self-published her memoir in Naples, Florida and though she has printed copies for family members, has also posted E-Book versions on a wesite for others to read. Congratulations, Mary! This is an admirable achievement and will be appreciated by many. I have posted a link to the left of this post.

Now I will investigate the possibility of an E-Book publisher for my memoir. Are you considering an E-Book for yours?

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Pit Lit and Writing Your Memoir

I sat riveted to the TV last night watching with the world as the 33 Chilean miners were rescued at the San Jose mine. While overcome with awe and joy, I also thought: What an incredible story! Sure enough, among the journalists given free access during the miners' 70 days of entombment, one has announced a book deal already. Jonathan Franklin of The Guardian will have his book "33 Men" published by Transworld in 2011.Other TV, book and movie rights are pending.

Then I felt depressed. My lifestory isn’t nearly as engaging, dramatic or unusual as those stories. Who would want to read my story when they could read a Pit Lit memoir? Why bother telling my boring little tale?

After I’d cried a bit and given myself a little shake, I thought about it. I’m not famous. I don’t have authors bugging me to ghost write my autobiography. But, if I didn’t tell my story, who would? The fact is : my life is my story, no one else’s. I’m the only one who can tell it my way. My brothers have their own take on our shared histories. My sister who is 10 years younger, has her story. My parents’ stories are their stories and form only the backdrop to my own.

It’s difficult to give yourself permission to write or continue writing your memoir. It’s a contract with yourself that has to be renewed daily. We play little games to trick ourselves into writing. I’ll just write it down. Maybe I will cut it out later. Pretend that this is a story in the 3rd person and what is happening is happening to another girl, not to you.

When we do this and produce a scene or two, we are still self-critical and often tempted to chuck it. The best thing to do is wait. Put it aside and wait a day, a week or months. Often in the fresh light of another day , what we thought was garbage, now looks brilliant, or at least salvageable for a first draft of our memoir. The lesson here is to write, keep writing, and save everything. You may not in the end, have a memoir like one of the Chilean miners, but you will have your memoir and someone will want to read it. You may be surprised how many.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Then I felt depressed. My lifestory isn’t nearly as engaging, dramatic or unusual as those stories. Who would want to read my story when they could read a Pit Lit memoir? Why bother telling my boring little tale?

After I’d cried a bit and given myself a little shake, I thought about it. I’m not famous. I don’t have authors bugging me to ghost write my autobiography. But, if I didn’t tell my story, who would? The fact is : my life is my story, no one else’s. I’m the only one who can tell it my way. My brothers have their own take on our shared histories. My sister who is 10 years younger, has her story. My parents’ stories are their stories and form only the backdrop to my own.

It’s difficult to give yourself permission to write or continue writing your memoir. It’s a contract with yourself that has to be renewed daily. We play little games to trick ourselves into writing. I’ll just write it down. Maybe I will cut it out later. Pretend that this is a story in the 3rd person and what is happening is happening to another girl, not to you.

When we do this and produce a scene or two, we are still self-critical and often tempted to chuck it. The best thing to do is wait. Put it aside and wait a day, a week or months. Often in the fresh light of another day , what we thought was garbage, now looks brilliant, or at least salvageable for a first draft of our memoir. The lesson here is to write, keep writing, and save everything. You may not in the end, have a memoir like one of the Chilean miners, but you will have your memoir and someone will want to read it. You may be surprised how many.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

" Life Goes On But Your Memoir Mustn't"

After attending a two-day workshop last week called “Illuminating the Path: Finding Theme and Structure in Your Memoir” with Allyson Latta, I try to sort out my notes, my thoughts and wonder how it all applies to my story.

“Life goes on but your memoir mustn’t”, a quote from Adair Lara in Writer’s Digest, became our mantra and challenge. Where do I start and finish my story? How do I construct the narrative arc of my story?

Should I begin chronologically with my early life on Charles Street then move on to the suburbs and what develops there? Or should I start with the move, flash back to longing for my early life in the rooming house, then move on to the crisis, climax and resolution? Another possibility is to start with moving back to the city for university (in the neighbourhood of Charles Street), then reflect on memories of my early years. I wasn’t planning to write about this period in university but my writing group tend to favour this approach. I had another idea about my life on Charles Street but I think this would work better as a short story, so I will set that option aside.

According to Adair Lara and Tristine Rainer, to figure out the narrative arc, the emotional framework of your memoir, you must figure out ‘the desire line’. What is it that you want? This is what drives the narrative and moves the character to the conclusion. In “Elements of Effective Arc” (Writer's Digest July/August 2010)Adair Lara suggests jotting down a list of actions and obstacles:

I wanted _______________ (the desire line).

To get it I______________ (action).

To get it, I then____________ (action)

But ______________ (obstacle) got in my way.

So, I _____________________ (action).

(And so on.)

When I look at this framework, I think that my over arching desire line was to go home again, ie. to go back to the place where I felt confident and secure. What I need to do now is to examine each scene of my memoir and identify my desire line, actions and obstacles for each step of my journey.

Have you identified your ‘desire line’?

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

“Life goes on but your memoir mustn’t”, a quote from Adair Lara in Writer’s Digest, became our mantra and challenge. Where do I start and finish my story? How do I construct the narrative arc of my story?

Should I begin chronologically with my early life on Charles Street then move on to the suburbs and what develops there? Or should I start with the move, flash back to longing for my early life in the rooming house, then move on to the crisis, climax and resolution? Another possibility is to start with moving back to the city for university (in the neighbourhood of Charles Street), then reflect on memories of my early years. I wasn’t planning to write about this period in university but my writing group tend to favour this approach. I had another idea about my life on Charles Street but I think this would work better as a short story, so I will set that option aside.

According to Adair Lara and Tristine Rainer, to figure out the narrative arc, the emotional framework of your memoir, you must figure out ‘the desire line’. What is it that you want? This is what drives the narrative and moves the character to the conclusion. In “Elements of Effective Arc” (Writer's Digest July/August 2010)Adair Lara suggests jotting down a list of actions and obstacles:

I wanted _______________ (the desire line).

To get it I______________ (action).

To get it, I then____________ (action)

But ______________ (obstacle) got in my way.

So, I _____________________ (action).

(And so on.)

When I look at this framework, I think that my over arching desire line was to go home again, ie. to go back to the place where I felt confident and secure. What I need to do now is to examine each scene of my memoir and identify my desire line, actions and obstacles for each step of my journey.

Have you identified your ‘desire line’?

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

The Power of a Family Secret

My personal essay The Power of A Family Secret has now been posted on Allyson Latta's new website. This essay appeared in an earlier version in several blog posts on this site. Please click on the title of my essay or Allyson's name, have a look and let me know what you think.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Letter to My Dead Great-Aunt Part Three

My mother told me Uncle John didn’t like to spend money but as your next of kin, he would have been the one responsible for your burial. I wondered if he had done nothing to commemorate your life. Maybe your body was never recovered. Maybe he was too overcome with grief. I wished I had asked Auntie Huckan, his wife but I hadn’t known about you then. I wished my mother had asked her but she didn’t think to ask. I found the details of your burial by chance and more details on your Death Certificate.

Armed with the name of the hotel where you died and the exact date of the fire, I pressed on and tried to find a photograph of the building. The Riverview Hotel had been built in 1906 or earlier (Henderson Directory 1906) and a large 1-storey addition of wood construction had been added in 1914. The Winnipeg architect, Charles S. Bridgeman designed it for the owner, J.J. O'Connell in 1913. No photograph was found but an interesting discovery showed up in the city records.

Negligence

I discovered on the Building Permit for the addition, the owner J.J. O'Connell had on June 11, 1914 been “convicted and reprimanded for not complying with Notice issued January 7, 1914 re Exit doors”. A Building Inspector had deemed the building dangerous four years before the fire! Maybe even before you were hired.

The Historical Buildings Officer for Winnipeg sent me several newspaper clippings about the fire on the night of February 5, 1918 when the Riverview Hotel burned to the ground. Three perished in the fire: a nurse employed by the owner, a veteran of WWI and you, my dear Great-Aunt Michalena, described as “Lena Wuchan, kitchen girl” and “Lena Guchan, kitchen maid”. They couldn’t even spell your name right.

Here’s what happened as I can piece it together from the clippings. Early in the morning on the 5th of February about 3:30 a.m. a fire broke out, possibly in the kitchen of the Riverview Hotel. Fanned by 30 mile an hour gale force winds, the fire quickly spread to nearby buildings. Five fire brigades responded promptly though there were 6-8 other fires in Winnipeg at that night. The Riverview Hotel was leveled within an hour. Total damage was estimated to be $180,000.

A neighbor called the fire department. Everyone was asleep when the alarm bells in each room went off. You were last seen in your room on the second floor. Smoke poured into the rooms and the stairs were blocked by dense smoke. The hotel owner, his wife and six children were sleeping on the first floor and all escaped unharmed except for smoke inhalation. Mr. O’Connell later told the press of the frantic attempts to escape by those who died. I can only try to imagine the terror you felt when you realized there was no way out.

Your body was found in the ashes two days later near the centre of the basement buried several feet beneath the debris. They believed these were your remains because they were found in the location of your room in the building. But you were found in the basement, because all three stories collapsed. Identification of the three victims was based on location of the bodies when found. A fourth victim died later in hospital.

The inquest a week later found no fault lay on the shoulders of the hotel owner or the fire department for the deaths, despite the fact that the building hadn’t been inspected for a year.

And so dear Auntie, this is your story, the evidence that you lived and died in Winnipeg in a tragic hotel fire that cold February night in 1918. There are still some gaps and incomplete knowledge of your short life. I promise you I will continue to search for more details, such as your immigration records and whatever vital records exist in Winnipeg or your ancestral village of Repuzhintsy. My cousins and I will be replacing the numbered stone on your grave with a personal memorial stone. I will honour your life by telling your story to all who will listen. I will never forget you and other immigrants who lost their lives in accidents and unsafe working conditions, trying to build a better life and a brighter future in Canada.

May your soul rest in peace. Vichnaya Pamiat.

love from your Grandniece,

Ruth

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Armed with the name of the hotel where you died and the exact date of the fire, I pressed on and tried to find a photograph of the building. The Riverview Hotel had been built in 1906 or earlier (Henderson Directory 1906) and a large 1-storey addition of wood construction had been added in 1914. The Winnipeg architect, Charles S. Bridgeman designed it for the owner, J.J. O'Connell in 1913. No photograph was found but an interesting discovery showed up in the city records.

Negligence

I discovered on the Building Permit for the addition, the owner J.J. O'Connell had on June 11, 1914 been “convicted and reprimanded for not complying with Notice issued January 7, 1914 re Exit doors”. A Building Inspector had deemed the building dangerous four years before the fire! Maybe even before you were hired.

The Historical Buildings Officer for Winnipeg sent me several newspaper clippings about the fire on the night of February 5, 1918 when the Riverview Hotel burned to the ground. Three perished in the fire: a nurse employed by the owner, a veteran of WWI and you, my dear Great-Aunt Michalena, described as “Lena Wuchan, kitchen girl” and “Lena Guchan, kitchen maid”. They couldn’t even spell your name right.

|

| Riverview Hotel 322 Nairn Avenue Elmwood, Manitoba |

A neighbor called the fire department. Everyone was asleep when the alarm bells in each room went off. You were last seen in your room on the second floor. Smoke poured into the rooms and the stairs were blocked by dense smoke. The hotel owner, his wife and six children were sleeping on the first floor and all escaped unharmed except for smoke inhalation. Mr. O’Connell later told the press of the frantic attempts to escape by those who died. I can only try to imagine the terror you felt when you realized there was no way out.

Your body was found in the ashes two days later near the centre of the basement buried several feet beneath the debris. They believed these were your remains because they were found in the location of your room in the building. But you were found in the basement, because all three stories collapsed. Identification of the three victims was based on location of the bodies when found. A fourth victim died later in hospital.

The inquest a week later found no fault lay on the shoulders of the hotel owner or the fire department for the deaths, despite the fact that the building hadn’t been inspected for a year.

|

| Newspaper Clippings from Winnipeg Firefighters Museum 1918 |

And so dear Auntie, this is your story, the evidence that you lived and died in Winnipeg in a tragic hotel fire that cold February night in 1918. There are still some gaps and incomplete knowledge of your short life. I promise you I will continue to search for more details, such as your immigration records and whatever vital records exist in Winnipeg or your ancestral village of Repuzhintsy. My cousins and I will be replacing the numbered stone on your grave with a personal memorial stone. I will honour your life by telling your story to all who will listen. I will never forget you and other immigrants who lost their lives in accidents and unsafe working conditions, trying to build a better life and a brighter future in Canada.

May your soul rest in peace. Vichnaya Pamiat.

love from your Grandniece,

Ruth

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Letter to My Dead Great-Aunt Part Two

The family story I heard from Mother and her sister Anne is that you were working at a hotel in Winnipeg saving your money to be married to your unnamed fiancé in the photograph. When fire broke out, you escaped somehow but ran back in to retrieve your $800 hidden under your mattress. You never came out. Were you overcome by smoke in that firetrap? Did the fire spread much faster than you anticipated? Or were you just a naïve girl who didn’t understand the danger and could only think of your hard-earned savings and your future going up in smoke? Eight hundred dollars in today’s dollars would be a lot of money. Brave or foolish, you lost your life in that fire.

I searched for a long time for your death and burial records. I searched newspapers for reports of a hotel fire but there were many hotel fires in Winnipeg in those days especially in the long cold winters. Photos are legend.

My cousin Ellen and I searched through countless cemetery lists until one day I found an on-line listing of Winnipeg City cemeteries and was able to find a listing for a “Lena Huekow” who died 2/5/1918. Confident this must be you, I contacted the City of Winnipeg who told me that they had no record of a “Michalena Huckan” but did have a “Lena Huckow” buried in Brookside Cemetery. My cousin Edith later confirmed that at last we had found your final resting place right next to the casualties of WW I. Further research revealed the name of the hotel, Riverview, (on the Red River) and the address, 322 Nairn Avenue in Elmwood. Finally I was able to obtain your Death Certificate. I requested the Coroner’s report but the records had been destroyed.

What would it have meant to me if you had lived, Michalena? You might have been like a Baba to me. I never knew my Baba, your sister. She died when I was 2 ½ . I saw her only once when I was 1 ½ and have no memory of the visit or her. You were 13 years younger so I might have known you. Maybe you would have moved to Oshawa where your older brother John lived for many years. He also died before I was born but his wife lived for many years. I knew her well and in fact was named, Frances, after her.

The only photos I have of Baba are taken when she was older, aged and toothless before her time. When I look at photos of my grandmother, your older sister Marya and you, Michalena, I see what she must have looked like as a young girl. I think she must have been as pretty as you when she was a young woman. I feel closer to her somehow. Closer to her youth.

To be continued...

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

I searched for a long time for your death and burial records. I searched newspapers for reports of a hotel fire but there were many hotel fires in Winnipeg in those days especially in the long cold winters. Photos are legend.

|

| Scott Bathgate - February 15, 1917 K. Elder Collection The Firefighters Museum of Winnipeg |

What would it have meant to me if you had lived, Michalena? You might have been like a Baba to me. I never knew my Baba, your sister. She died when I was 2 ½ . I saw her only once when I was 1 ½ and have no memory of the visit or her. You were 13 years younger so I might have known you. Maybe you would have moved to Oshawa where your older brother John lived for many years. He also died before I was born but his wife lived for many years. I knew her well and in fact was named, Frances, after her.

|

| John Huckan and Frances Ross Huckan Winnipeg, Manitoba c. 1914 |

The only photos I have of Baba are taken when she was older, aged and toothless before her time. When I look at photos of my grandmother, your older sister Marya and you, Michalena, I see what she must have looked like as a young girl. I think she must have been as pretty as you when she was a young woman. I feel closer to her somehow. Closer to her youth.

|

| Marya Huckan Zarecka Sclater, Manitoba c.1940 |

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Letter to My Dead Great-Aunt

About two years ago I was inspired by Sheila Nevins to write a letter to my dead Great-Aunt who died tragically in a hotel fire in Winnipeg in 1918. Michalena Huckan, my maternal Baba's much younger sister, immigrated to Canada in @ 1910-11 and was engaged to be married. The family story is that the upper storey of the building collapsed on her when she ran back to retrieve her savings hidden under the mattress. My nearly 97 year old mother still remembers her mother crying for days when she heard the news. Where Michalena was buried became a mystery. She had become a ghost haunting our family.

___________________________________________

Dear Great-Aunt Michelena or maybe I should call you Вуйна,

Ever since I saw your photograph and heard your heart-rending story, I have been obsessed with finding traces of your short life. The journey has been frustrating as women are much harder to track. Invisible threads in our past history. My history.

Michalena, you were about 13 years younger than your older sister, my grandmother Marya Zarecka. Before I knew the exact age difference, I wondered if you might be her illegitimate daughter and the reason behind my grandfather's relentless anger towards his wife. One day I asked my mother timidly if that could be possible. "No!" she stated, "they were sisters." I believe you were.

You were born in 1893 in the village of Repuzhintsy, province of Bukovina when it was part of Roumania, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. You were 18 when Marya left for Canada to join my grandfather in 1911 with her two children Helena and Anton. Maybe you came with her or followed later. I have not found your immigration records yet.

Your brother Iwan (John) immigrated to Winnipeg with his family in 1914. You went to Winnipeg and, according to the Henderson Directory, by 1916 you were living in Ben Nevis House, a rooming house at 42 Dagmar Street. Like so many hundreds of other young single immigrant women, you were working in one of the many downtown Winnipeg hotels.

I have two studio photographs of Michalena, likely taken after her brother arrived in 1914. In one she is looking very proper, with her fiancé, her brothers Nikolaj, Iwan, his wife and daughter.

Your fiancé is standing beside you in the group photograph. You must have been looking forward to marrying him. You risked your life for the sake of $800 you saved and kept hidden under your mattress. Who was he? We don't even know his name, though most likely he was from your village, Repuzhintsy. Was he heart-broken when he heard the news of your death? Did he ever recover from the loss? Perhaps he married and had children. Where are his descendents now? Would they recognize him in this photograph?

In the other photograph, you stand beside a table, hair flowing , looking very beautiful. I can see that you were a pretty woman, short in stature with long curly brown hair. Your eyes are lighter than brown, blue or hazel perhaps. You are wearing a long sleeved white blouse and a long dark skirt, proper formal female attire for the time. You are wearing no visible jewelry except a pin at the neck of your blouse. Your hands appear to be strong but graceful, holding a small bouquet of flowers.

To be continued...

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

___________________________________________

Dear Great-Aunt Michelena or maybe I should call you Вуйна,

Ever since I saw your photograph and heard your heart-rending story, I have been obsessed with finding traces of your short life. The journey has been frustrating as women are much harder to track. Invisible threads in our past history. My history.

Michalena, you were about 13 years younger than your older sister, my grandmother Marya Zarecka. Before I knew the exact age difference, I wondered if you might be her illegitimate daughter and the reason behind my grandfather's relentless anger towards his wife. One day I asked my mother timidly if that could be possible. "No!" she stated, "they were sisters." I believe you were.

You were born in 1893 in the village of Repuzhintsy, province of Bukovina when it was part of Roumania, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. You were 18 when Marya left for Canada to join my grandfather in 1911 with her two children Helena and Anton. Maybe you came with her or followed later. I have not found your immigration records yet.

Your brother Iwan (John) immigrated to Winnipeg with his family in 1914. You went to Winnipeg and, according to the Henderson Directory, by 1916 you were living in Ben Nevis House, a rooming house at 42 Dagmar Street. Like so many hundreds of other young single immigrant women, you were working in one of the many downtown Winnipeg hotels.

I have two studio photographs of Michalena, likely taken after her brother arrived in 1914. In one she is looking very proper, with her fiancé, her brothers Nikolaj, Iwan, his wife and daughter.

Your fiancé is standing beside you in the group photograph. You must have been looking forward to marrying him. You risked your life for the sake of $800 you saved and kept hidden under your mattress. Who was he? We don't even know his name, though most likely he was from your village, Repuzhintsy. Was he heart-broken when he heard the news of your death? Did he ever recover from the loss? Perhaps he married and had children. Where are his descendents now? Would they recognize him in this photograph?

|

| Michalena Huckan, her fiancé, Nikolaj Huckan Franciszka Ross Huckan, Wladzia (Frances), Iwan (John) Huckan Winnipeg, Manitoba c. 1914 |

In the other photograph, you stand beside a table, hair flowing , looking very beautiful. I can see that you were a pretty woman, short in stature with long curly brown hair. Your eyes are lighter than brown, blue or hazel perhaps. You are wearing a long sleeved white blouse and a long dark skirt, proper formal female attire for the time. You are wearing no visible jewelry except a pin at the neck of your blouse. Your hands appear to be strong but graceful, holding a small bouquet of flowers.

|

| Michalena Huckan Winnipeg, Manitoba c. 1914 |

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

BOTH WAYS IS THE ONLY WAY I WANT IT by Maile Meloy

Maile Meloy is a young American writer I’d never heard of before my son gave me a book of her short stories for Christmas last year. I only got down to it recently in my beside pile. I was sorry I’d delayed reading it.

The title of the book “Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It”, taken from a short poem by A. R. Ammons, is the theme of her eleven short stories set mostly in Montana where she grew up. All the characters want it both ways in tricky emotional or sexual circumstances. All are caught in a dilemma of sorts. What is the socially or morally right thing to do versus what does the character want to do?

The title of the book “Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It”, taken from a short poem by A. R. Ammons, is the theme of her eleven short stories set mostly in Montana where she grew up. All the characters want it both ways in tricky emotional or sexual circumstances. All are caught in a dilemma of sorts. What is the socially or morally right thing to do versus what does the character want to do?

In “Travis B.”, a young ranch hand with a gimpy leg falls in love with a young lawyer who commutes 9 ½ hours to town to teach a class he chanced to wander into. In “Two-Step” female friends discuss one’s husband’s infidelity while the reader squirms realizing that the ‘other woman’ is one of them. The author doesn’t shy away from unsavory, slightly creepy motivations and feelings that are part of her characters' lives. The stories are layered and rich with details.

All the stories have a tension that makes the reader uneasy. The dialogue carries the story and makes the reader feel like a fly stuck to flypaper, wanting to leave, but compelled to stay. Having first observed particular details, the author paints her characters with a few deft strokes leaving an indelible impression on the reader. Her spare and fast-paced prose takes the reader along for a thrilling ride to a surprise conclusion.

Maile enjoys writing short stories where the way out leads to an ending that opens possibilities. She is the author of two story collections and two novels.

NPR Interview with Maile Meloy

The Writers Circle of Durham Blog: Reading As Writers

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

The title of the book “Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It”, taken from a short poem by A. R. Ammons, is the theme of her eleven short stories set mostly in Montana where she grew up. All the characters want it both ways in tricky emotional or sexual circumstances. All are caught in a dilemma of sorts. What is the socially or morally right thing to do versus what does the character want to do?

The title of the book “Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It”, taken from a short poem by A. R. Ammons, is the theme of her eleven short stories set mostly in Montana where she grew up. All the characters want it both ways in tricky emotional or sexual circumstances. All are caught in a dilemma of sorts. What is the socially or morally right thing to do versus what does the character want to do? In “Travis B.”, a young ranch hand with a gimpy leg falls in love with a young lawyer who commutes 9 ½ hours to town to teach a class he chanced to wander into. In “Two-Step” female friends discuss one’s husband’s infidelity while the reader squirms realizing that the ‘other woman’ is one of them. The author doesn’t shy away from unsavory, slightly creepy motivations and feelings that are part of her characters' lives. The stories are layered and rich with details.

All the stories have a tension that makes the reader uneasy. The dialogue carries the story and makes the reader feel like a fly stuck to flypaper, wanting to leave, but compelled to stay. Having first observed particular details, the author paints her characters with a few deft strokes leaving an indelible impression on the reader. Her spare and fast-paced prose takes the reader along for a thrilling ride to a surprise conclusion.

Maile enjoys writing short stories where the way out leads to an ending that opens possibilities. She is the author of two story collections and two novels.

NPR Interview with Maile Meloy

The Writers Circle of Durham Blog: Reading As Writers

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

In Honour of Father's Day: A Story About My Dad

“Jimmy, come quick, Dad’s cooking!”

“Dad’s cooking?” My brother knew something was up. Mom always did the cooking at our house.

“Yeah, come on, let’s watch him. He’s making french fries!”

We dashed into the house and sank down on the vinyl chairs around the arborite table. Dad stood in the middle of the kitchen, a tea towel tucked around his pants, like a chef. Holding a few potatoes in one hand, a paring knife in the other, he dropped them into the enamel sink and ran the cold water. After peeling them, he moved to a cutting board on the table and stood over the pile. Without saying a word, he began to slice the potatoes into layers and sliver them into long squared pieces, carefully dropping them into cold water as he worked. His rough fingers, plump like sausages, were more used to manual labour than food preparation. In the days before frozen supermarket fries, he amazed us by replicating what we’d only seen in restaurants.

In fact, Dad had worked as a short-order cook. In the 1930s, after riding the rails to New Brunswick and back to Manitoba, a sawmill foreman told him to “get a trade”, to make something of himself. When he first arrived in Toronto, he waitered occasionally at the Savarin Hotel while taking welding courses at night. One night, the owner of Hunt’s Restaurant offered him a training course and steady job at $7.00 a week. Dad accepted because welding jobs were still scarce. He worked for Hunt’s for 5 years, moving from a kitchen on Mount Pleasant Road, to another at St. Clair and Oakwood, and finally, to College and Dovercourt, increasing his pay by $1.00 a week with each move and advancing to manager. In those days, you could get Today’s Special, a complete meal, for 35 cents! In 1939, when wartime created industrial jobs, Dad moved on to welding and never looked back. Except for these odd moments of culinary inspiration.

Sometimes when preparing french fries Dad used the sunken burner and deep pot in the back left corner of the electric range. This time, he bent over the pot cupboard, pulled the deep-fryer from the back and poured in the oil. After bringing it to a boil, he carefully lowered the basket of raw potatoes into the yellow bubbles, his eyes fixed on the pot. Sometimes he would par-boil them and set the potatoes aside to be finished off to a golden brown at the last moment before eating. All four of us sat entranced with the entire process, nostrils filled with the heady smell of frying oil, our mouths open and watering, impatient to taste his masterpiece.

Mom remained in the background while Dad cooked, only emerging at the end to hand us the malt vinegar, salt and ketchup and slip in a vegetable and a few slices of meat to complete the meal.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

My Writing Group: Life Writers Ink

In the May/June issue of The Word Weaver - the newsletter for The Writers' Circle of Durham Region - is an article on page 3 by Mary McIntyre about our writing group, Life Writer's Ink. Please have a look.

The Road: To Milo

I struggled with the idea of writing something to read at Milo’s funeral. I had never been able to speak at a funeral, even my father’s. I always feared tears would overwhelm me and erase anything I might be trying to say. My husband’s urgings just served to make me more anxious. “I can’t write under pressure! I’m not a Hallmark writer. I work to an inner rhythm”.

I wanted to write something for her, for my step-daughter, my daughter, whom I came to love and admire after over 40 years. The step-daughter who was 5 years older than my first child and forced me to parent her before I was ready. When she hit puberty and needed guidance, I was still dealing with my son’s childhood issues, baseball, summer camp, and public school. Scrambling, I did buy her first bra, bought books explaining the ‘facts of life’ and tried to offer what help I could since she lived with her mother in Toronto and only spent alternate weekends and some holidays with us.

Over the five days in Edmonton I worked on a poem using random notes I had written on the plane. I didn’t know where I was going with it but I knew I wanted it to be a tribute to her strengths. By the night before the funeral, I wasn’t happy with the ending and felt unsure about reading it. Then I realized that was symbolic for all that had happened. I wasn’t happy with her life ending prematurely either. So I read it as is. Perhaps I will tweak it further. Perhaps not.

To Milo

Milo, named for an actress you never knew,

You trekked your bumpy way

Into our lives, our hearts.

Resilient, smiling, resolute,

You navigated two worlds,

Careful never to misstep

The line between country and city.

From school to school, then college.

On to parenthood before we knew it.

Dark years left behind

Out shadowed by baby light,

Travel, another child,

The petite daughter to complete your family,

Submerged in happy domesticity.

More years of turmoil:

You made choices to survive,

Protect your chicks,

Rise above sorrow, grief,

Your mother’s passing.

Seven years in South Dakota brightened life,

College beckoned.

Happiness broke through in snatches.

Back to Alberta, familiar ground

Where you lost and found love.

All the while a mother,

The finest of mothers.

We grieve now with your children,

Almost grown.

Raised and ready

To catch that cold north wind,

Change it into honeyed breezes.

With thoughts of you:

Whispering, directing,

Guiding, giggling,

Quizzing, questioning,

Always loving.

We grieve with the love that appeared,

The one who slipped in,

Grabbed you unawares,

Not knowing you had so little time.

We grieve as parents,

Our daughter lost,

Not meant to outlive our children.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

I wanted to write something for her, for my step-daughter, my daughter, whom I came to love and admire after over 40 years. The step-daughter who was 5 years older than my first child and forced me to parent her before I was ready. When she hit puberty and needed guidance, I was still dealing with my son’s childhood issues, baseball, summer camp, and public school. Scrambling, I did buy her first bra, bought books explaining the ‘facts of life’ and tried to offer what help I could since she lived with her mother in Toronto and only spent alternate weekends and some holidays with us.

Over the five days in Edmonton I worked on a poem using random notes I had written on the plane. I didn’t know where I was going with it but I knew I wanted it to be a tribute to her strengths. By the night before the funeral, I wasn’t happy with the ending and felt unsure about reading it. Then I realized that was symbolic for all that had happened. I wasn’t happy with her life ending prematurely either. So I read it as is. Perhaps I will tweak it further. Perhaps not.

To Milo

Milo, named for an actress you never knew,

You trekked your bumpy way

Into our lives, our hearts.

Resilient, smiling, resolute,

You navigated two worlds,

Careful never to misstep

The line between country and city.

From school to school, then college.

On to parenthood before we knew it.

Dark years left behind

Out shadowed by baby light,

Travel, another child,

The petite daughter to complete your family,

Submerged in happy domesticity.

More years of turmoil:

You made choices to survive,

Protect your chicks,

Rise above sorrow, grief,

Your mother’s passing.

Seven years in South Dakota brightened life,

College beckoned.

Happiness broke through in snatches.

Back to Alberta, familiar ground

Where you lost and found love.

All the while a mother,

The finest of mothers.

We grieve now with your children,

Almost grown.

Raised and ready

To catch that cold north wind,

Change it into honeyed breezes.

With thoughts of you:

Whispering, directing,

Guiding, giggling,

Quizzing, questioning,

Always loving.

We grieve with the love that appeared,

The one who slipped in,

Grabbed you unawares,

Not knowing you had so little time.

We grieve as parents,

Our daughter lost,

Not meant to outlive our children.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

The Scent of Lilacs

I was meeting a friend for lunch at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Hamilton on May 6th, 2010 when my husband called to tell me Milo had died. I kept saying “who?” “who died?”. The facts just wouldn’t sink in. “Not Milo!” In a daze I wandered into the foyer to find Marilyn who hadn’t arrived yet. I kept pacing back and forth from one end to the other looking for her. She finally appeared. I waited until we sat down to lunch before blurting out the news. She cried while I robotically repeated the words. We ordered and talked then she asked me if I wanted to go back home. “No,” I said. “I want to see the lilacs. Let’s walk.”

The Lilac Festival was the following weekend and the bushes were in their glory. Purples, mauves, pinks and whites of all species. The flowers never smelled so fragrant to me or looked so glorious. I savoured every inhalation and every vista. We walked slowly and I took many photographs. I thought of Milo and how she would never have this chance again. I thought about how fragile life is and how lucky I was to be able to experience the scent of lilac for another season. We walked and talked. I’m glad I took that time. After a few hours I was ready to drive home, call the airline and fly to Edmonton to face reality.

Losing a Daughter

Losing a daughter is like losing a piece of yourself, a part of your heart or your soul. This is true even when she was your step-daughter.

During the past weeks our family has been rocked by the sudden death of our daughter, Milo Jackson, at the age of 43. She had not been ill but suffered a fatal pulmonary embollism in her sleep on May 6, 2010. She was there in the evening and gone by morning. Twenty days later it seems like a bad dream. I still hope to wake up and find it was a mistake. It didn't really happen. But it did.

I met Milo when she was two years old, a smiling happy toddler. She spent every other weekend with us and holidays too. She was an active part of our family activities, rituals and celebrations. In this favourite photograph of her at about age four or five, she's holding her rabbit which we kept at the farm, and sitting at the piano. She loved playing the piano with Nonie, my husband's mother, whenever we were together.

While I was in Edmonton for the funeral I wrote a poem for Milo which I read during the service. I will be publishing it here as I write about this experience over the next few weeks. Thanks for being there and listening.

Anne Michaels Reads From THE WINTER VAULT

Anne Michaels steps to the microphone and I am enchanted by her mass of dark curly hair. Her voice draws me in with the weightiness and scope of her subject matter. This is no ordinary author reading. She’s not talking about a simple plotline and a quick read. This is a book to be savoured slowly and tenderly with each well-chosen word. The sensual images draw the reader in and bathe you in a dreamy cloud of emotion that lingers long after the book is closed.

I feel badly that I haven’t yet finished THE WINTER VAULT, but I find many others at the reading who also haven’t finished it. It’s a slow read, one that raises many emotional, moral and philosophical questions. It takes time to digest, to ruminate and figure out where we stand. The author tackles these tough issues head-on, but with intimate gentle language that engages the reader.

THE WINTER VAULT is a personal story, a love story, set in a larger historical context in three different settings, Ontario, Egypt and Poland. The historical contexts are the building of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950s, the building of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s and the rebuilding of Warsaw after the Second World War.

The moral and philosophical questions she raises are enormous: science vs. emotion, engineering vs. culture and humanity, the personal history of many vs. the legacy of an important person, authentic vs. recreated landscapes, replicas of cultural heritage vs. sites of heritage significance left ‘in situ’, true memory vs. rewritten tourist ‘history’, progress vs. stagnation, home vs. transience. And more.

I feel a personal connection to her questions from my work as a Historical Planner with the Ministry of Transportation in the 1980s-90s. The ‘mitigation’ solution for heritage resources never felt ‘right’ to me though it was the engineering solution to inconveniently located archaeological, natural or built heritage sites. Many years earlier in 1964, a visiting anthropology professor I met at a party invited me to come to Egypt and join a physical anthropology project. As the Nubian people were being displaced from their home for the building of the Aswan Dam, anthropologists were seizing the opportunity to take physical measurements of them. I felt squeamish and never went. Last year I wrote a poem about it.

Aswan: A Road Not Taken

The theme of The Winter Vault

reminds me of a night.

Was it ’64? maybe ’65.

A house party on Davenport.

Along the curve

towards Avenue Road.

Anthropologists.

Drinking too much.

Hopping over rooftops

Across the abyss, not noticing.

Some visiting professor

tries to persuade me to

come to Egypt.

The Aswan Dam is coming.

Nubians being relocated

-displaced actually-

A chance to measure

skulls and bodies.

For science.

No ethics approval required.

I apologize, stuttering something about

Grad school in the fall.

And wonder these years later:

what if I’d gone?

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

I feel badly that I haven’t yet finished THE WINTER VAULT, but I find many others at the reading who also haven’t finished it. It’s a slow read, one that raises many emotional, moral and philosophical questions. It takes time to digest, to ruminate and figure out where we stand. The author tackles these tough issues head-on, but with intimate gentle language that engages the reader.

THE WINTER VAULT is a personal story, a love story, set in a larger historical context in three different settings, Ontario, Egypt and Poland. The historical contexts are the building of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950s, the building of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s and the rebuilding of Warsaw after the Second World War.

The moral and philosophical questions she raises are enormous: science vs. emotion, engineering vs. culture and humanity, the personal history of many vs. the legacy of an important person, authentic vs. recreated landscapes, replicas of cultural heritage vs. sites of heritage significance left ‘in situ’, true memory vs. rewritten tourist ‘history’, progress vs. stagnation, home vs. transience. And more.

I feel a personal connection to her questions from my work as a Historical Planner with the Ministry of Transportation in the 1980s-90s. The ‘mitigation’ solution for heritage resources never felt ‘right’ to me though it was the engineering solution to inconveniently located archaeological, natural or built heritage sites. Many years earlier in 1964, a visiting anthropology professor I met at a party invited me to come to Egypt and join a physical anthropology project. As the Nubian people were being displaced from their home for the building of the Aswan Dam, anthropologists were seizing the opportunity to take physical measurements of them. I felt squeamish and never went. Last year I wrote a poem about it.

Aswan: A Road Not Taken

The theme of The Winter Vault

reminds me of a night.

Was it ’64? maybe ’65.

A house party on Davenport.

Along the curve

towards Avenue Road.

Anthropologists.

Drinking too much.

Hopping over rooftops

Across the abyss, not noticing.

Some visiting professor

tries to persuade me to

come to Egypt.

The Aswan Dam is coming.

Nubians being relocated

-displaced actually-

A chance to measure

skulls and bodies.

For science.

No ethics approval required.

I apologize, stuttering something about

Grad school in the fall.

And wonder these years later:

what if I’d gone?

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Moving From Memoir to Novel: Jane Boruszewski's Story ESCAPE FROM RUSSIA

“Your father was lucky to be living now in Canada, and you are lucky too” Janina wrote in one of her comments to me in a writing workshop. She knew all about luck: both the bad luck of being born in Poland in 1926, and the good luck of being a survivor. She was 13 when Stalin’s cruel regime deported her family and over a million and a half Poles from their homes to northern Kazakhstan, Siberia. On the way or during the first winters, many died of starvation including her father, an aunt, her sister, Helcia and a baby brother. She managed to survive the harsh life until the amnesty in 1942 when she left by train with her family to find the Polish Army. When she and her brother and sister contracted typhoid fever they were hospitalized in Bukhara (Uzbekistan) and were separated from the family. Again she survived, and was helped by the Polish Army to escape from Russia through the Caspian Sea to Persia (Iran) and ultimately to a Polish community in Tengeru, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), East Africa where she spent seven years completing high school. After the war ended, she signed up to work at a textile mill in England, where she met her future husband Walter, and later immigrated to America.

I’ve never forgotten Janina because she woke me up to the power of personal story telling to convey larger stories of human history. Janina or Jane Boruszewski was one of several aspiring writers who signed up for an on-line advanced memoir writing workshop with Allyson Latta in the fall of 2008. Jane was writing her memoir, in English, her second language. She had taken other courses and was fluent enough in English to begin writing her stories, seven of which were published in Oasis Journal. Compelled by a need to tell her life story, she continued writing until her death in August 2009, at the age of 82.

Jane’s personality was shaped by her extraordinary experiences. Her writing is important because it gives a human scale to the horrors and suffering of deportation and a life that most of us can’t imagine and have never experienced. She engages the reader by focusing on universal themes of family, love, hate, sickness and death. Then she slows down the narrative so that we can visualize a young couple in the glade in the taiga, and adds just enough context, that the dangers of their encounter are apparent. Too much context would lose the reader. Jane shows the reader what the characters are like with a skillful use of powerful verbs, subtle mention of small gestures or body language and terse bits of dialogue.

After Jane’s death, her husband, Walter Boruszewski, worked with Leila Joiner, editor of Oasis Journal and publisher of Imago Press and Pennywyse Press, to publish a novel based on Jane’s memoirs called ESCAPE FROM RUSSIA. The book is available from Amazon, and Barnes and Noble. Don’t miss it.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

I’ve never forgotten Janina because she woke me up to the power of personal story telling to convey larger stories of human history. Janina or Jane Boruszewski was one of several aspiring writers who signed up for an on-line advanced memoir writing workshop with Allyson Latta in the fall of 2008. Jane was writing her memoir, in English, her second language. She had taken other courses and was fluent enough in English to begin writing her stories, seven of which were published in Oasis Journal. Compelled by a need to tell her life story, she continued writing until her death in August 2009, at the age of 82.

Jane’s personality was shaped by her extraordinary experiences. Her writing is important because it gives a human scale to the horrors and suffering of deportation and a life that most of us can’t imagine and have never experienced. She engages the reader by focusing on universal themes of family, love, hate, sickness and death. Then she slows down the narrative so that we can visualize a young couple in the glade in the taiga, and adds just enough context, that the dangers of their encounter are apparent. Too much context would lose the reader. Jane shows the reader what the characters are like with a skillful use of powerful verbs, subtle mention of small gestures or body language and terse bits of dialogue.

After Jane’s death, her husband, Walter Boruszewski, worked with Leila Joiner, editor of Oasis Journal and publisher of Imago Press and Pennywyse Press, to publish a novel based on Jane’s memoirs called ESCAPE FROM RUSSIA. The book is available from Amazon, and Barnes and Noble. Don’t miss it.

Copyright © 2010, Ruth Zaryski Jackson

Even More on Family Secrets

After writing these posts I have been asked: “What sorts of things can become a family secret?” The short answer is: anything someone doesn’t want to talk about openly. Certainly there are always private concerns about your family you don’t share with your neighbours or friends. I’m not talking about this type of privacy: something that’s no one's business. But these are not secrets within the family. Everyone knows that old Uncle Harry is like that, whatever “that” is.

I’m talking about secrets that are hidden from others in the family because someone felt shame and thought it best not to talk openly about it. These secrets are then perpetuated down the generations.

What is considered a secret can vary by family, by culture, by ethnicity and by time. These secrets may be health issues e.g. epilepsy or mental retardation which wasn’t widely understood or accepted in the 19th and early 20th century. Or they could be some form of mental illness like schizophrenia or a bi-polar disorder which also wasn’t understood or accepted. Having a sick family member was perceived as a stain on the family and kept hidden.

Other secrets might be accidents or a death of a child if the circumstances were dodgy and the family felt guilty or responsible. Suicides were rarely mentioned but a trail to the truth can be found when Catholics or Greek Catholics were not buried in their own churchyards. Dementia wasn’t accepted by some families. Stories of family addictions, violence, abandonment, sexual abuse or incest were also rarely passed down or, if so, told in a way that diluted or denied any wrongdoing. Illegitimate children, adoption or raising someone else’s child might be kept hidden. Sexual philandering or divorce might be a secret. True sexual orientation might be denied and never discussed.

Sometimes certain hardships e.g. immigration and poverty were considered noble and some families talked about overcoming their humble beginnings. Other immigrants denied their roots and ethnicities, changing or Anglicizing their names when they moved to cities or needed a job.

Family proclivities for thievery or other illegal activities might become a family secret. Jail records or time unaccounted for may have been glossed over in the family story. A successful family might deny the origins of their financial gains during prohibition.

I heard of another kind of family secret when descendants of a family were trying to figure out their genealogy and family connections to a grandfather who had left a wife who didn't want to emigrate and his children in Europe. The man lived with another woman in Canada and raised a second family. Such a tangled web for his descendants to unravel.

After writing this post, I found a comprehensive piece by Dr. Allan Schwartz which explores Family Secrets. John Bradshaw has also written a book called: FAMILY SECRETS: THE PATH TO SELF-ACCEPTANCE AND REUNION.

I’m sure there are many more kinds of family secrets. Do you have any to add?

I’m talking about secrets that are hidden from others in the family because someone felt shame and thought it best not to talk openly about it. These secrets are then perpetuated down the generations.

What is considered a secret can vary by family, by culture, by ethnicity and by time. These secrets may be health issues e.g. epilepsy or mental retardation which wasn’t widely understood or accepted in the 19th and early 20th century. Or they could be some form of mental illness like schizophrenia or a bi-polar disorder which also wasn’t understood or accepted. Having a sick family member was perceived as a stain on the family and kept hidden.